Eleven years ago, baseball players walked off the field in protest for the first time in the seven-decade professional history of the game in Japan.

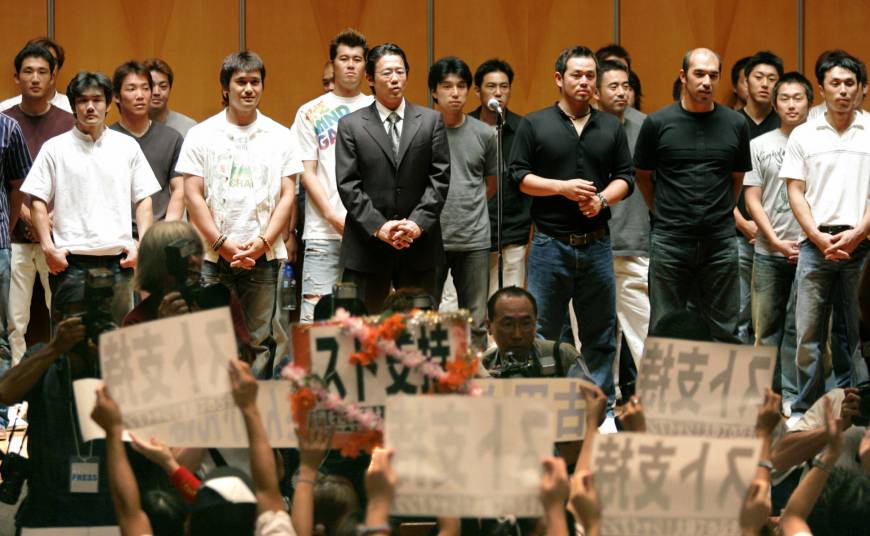

Owners wanted to consolidate two of the dozen pro teams, without offering a replacement. Players opposed the merger and were outraged that they had been kept out of the decision-making process. Atsuya Furuta of the Tokyo Yakult Swallows led collective bargaining on behalf of the Japan Professional Baseball Players Association union. Talks broke down and players struck six scheduled games over two days.

Players reached out to their fans with signing and photo events. Most fans sided with the striking players, but a vocal minority accused them of selfishness and having insulted their fans.

It always strikes me as odd how striking workers — rather than stubborn bosses — are often the ones accused of greed. The players did not take the decision to strike lightly; they had agonized over the decision and certainly were not taking their fans for granted. They made impassioned appeals to the fans that a strike was the only way they could save the wonderful spirit of the game.

I vividly remember Furuta being interviewed on live TV. A fan told him to take care of his health and Furuta broke down in tears. He had been under such extraordinary pressure going up against an almost unimaginably powerful management, both in negotiations and then through a labor dispute. The players endured a great deal of physical and mental stress, not just due to pressure from the owners, but also from the media, which took a dim view indeed of uppity unionists daring to exercise their constitutional right to strike. The dispute was settled on Sept. 23, 2004, when owners backed down and agreed to establish a new franchise and keep the number of teams at an even dozen.

Japan is known for treating the customer as king (or god?). Recently the notion that Japan has some magically unique custom of hospitality (omotenashi) has been gaining traction in the public imagination. In such a climate, it’s no surprise that strikers are increasingly vilified in the media and in many sections of public opinion.

The scorn is even more intense when an industrial dispute involves schoolteachers. Teachers who strike are disregarding their students, critics say: Surely they should prioritize educating their students over the trivial matter of their own working conditions?

If you have read any of my columns, you will already know that I disagree. Teachers are workers who happen to provide the service of education. Teachers at public schools are government employees whose right to strike is prohibited under laws for civil servants. The lack of that right is a serious issue in its own right, but this month I will set that aside to focus on an extraordinary case of language teachers who struck for better conditions and demonstrated why the right to strike is so important to workers.

Let’s go further back than the baseball walkout, to 18 years ago. Nichibei Eigo Gakuin is an English language school chain headquartered in Osaka with branches in Kansai and Kanto. On Aug. 25, 1997, 28 teachers and staff declared a new union to the firm’s management, demanding collective bargaining (CB).

The union was chaired by Paul Dorey, an instructor with the school. Dorey, from the U.K., was on one-year fixed-term contracts, renewed year after year, as is so often the case for foreign language teachers in Japan. He joined the General Union, which is affiliated with the National Union of General Workers, and set up a Nichibei GU branch.

“Generally speaking, working conditions started deteriorating from around 1994, along with the arrival of an aggressive new vice-president,” Dorey explained to me recently. “One new teacher warned us that the vice-president had told him that she intended to ‘phase out’ the older teachers. This confirmed what we already sensed. By 1997 we felt we had nothing to lose.”

Dorey and his fellow union members decided to research their legal rights. Branch vice-chair Yukio Shimodaira discovered that they were due paid holidays, as all workers are under the law. The union claims the school had not informed them of their rights to these holidays. Dorey says the new information collected by Shimodaira became a powerful recruiting tool, since many coworkers were also unaware of their rights.

Dorey also says that Japanese administrative staff were working overtime without getting paid. Sābisu zangyō (“service overtime” — effectively, working for free) is endemic in modern Japan. So, the union demanded that overtime be paid.

Many unions that recruit foreign language teachers find there is little solidarity between Japanese administrative staff and foreign teachers. In my experience, it seems that management at least permits — and in some cases, encourages — a strict segregation between the two groups of workers: a form of divide and conquer. Dorey and his comrades at Nichibei Eigo somehow managed to knock down that wall and build solidarity across this professional and cultural divide. That alone is an accomplishment anyone involved in language school unions today will know is remarkable.

The school may have feared such a strong show of solidarity. The union alleges that the school then began to harass union members. A series of CB sessions led nowhere. The union decided to strike over their demands (which included a pay hike — a demand that remains unresolved to this day). Language teachers in Japan usually strike full lessons, so that’s what the Nichibei Eigo teachers did. Management, however, made sure to have strike-breakers standing by to cover struck classes.

With no hope of a breakthrough, the union decided they had no choice but to strike partial classes. For example, they would strike 15 minutes in the middle of a 40-minute lesson. The union gave very little notice of the strike before each class — seconds in some cases. This made it difficult, to say the least, for management to cover the strike, since they had to send in the strike-breaker for just 15 minutes. Imagine it from the students’ point of view: The lesson starts with one teacher who leaves in the middle for a strike then returns to complete the lesson.

“Partial class strikes was a tactic that we were forced to use because of scabs,” says current General Union chair Dennis Tesolat, using a pejorative for workers who break strikes. “The company interfered in our right to strike by trying to neutralize them using scabs. We would strike the day, they scabbed. We’d strike a whole class, they’d scab. We’d strike the beginning or end, they’d scab. If we wanted to protect our right to strike, we had no other choice.”

The school apparently could not brook such an assertion of rights. Management first removed Dorey from group lessons and reduced the number of koma (lesson units) that he taught. The union alleges the company then also warned students that Dorey might strike, so as to discourage them from scheduling private lessons with him. The management then dismissed Dorey, claiming he was uncooperative with administrative staff (ironic considering the solidarity that they had built) and citing his “productivity rate” (kadōritsu), which had fallen below 50 percent. Of course, it was management that had helped reduce his class load. The school also fired two more teachers who were part of the union.

Dorey sued the firm, claiming abuse of the right to strike and that the company’s purpose was to crush the union. He also demanded unpaid back wages.

On March 2, 2000, Osaka District Court ruled in Dorey’s favor on all points. The court surmised that it was reasonable to expect that some students preferred that their teacher refrain from striking. Therefore, a drop in private lessons and thus a declining productivity ratio had been unavoidable. Under such circumstances, the court said, dismissing Dorey due to a reduction in his class load amounted to a restriction on his right to strike. In conclusion, the cause of the dismissal was the strike and the firing was therefore an “unfair labor practice” — jargon for a violation of the Trade Union Law.

The court also recognized that the school’s removing Dorey from group lessons and discouraging students from booking private lessons with him had pushed down his productivity rate, again making any firing illegitimate in the eyes of the court. The school appealed to the Osaka High Court, which upheld the original ruling on Nov. 7 the same year.

The school had used the will of the students as a defense against the strikes in court, but many of Dorey’s students signed affidavits praising his classes as well as his character. Students supported a worker with the courage and conviction to fight to realize his demands. I think that in this case, it was the students rather than management who learned the most about the meaning of the right to strike.

General Union’s victories in 2000 against Nichibei Eigo Gakuin in court — and in labor commission rulings a year later over the other two dismissals — came up in the court case brought by management over the Berlitz strike of 2007-08, in which the firm challenged the legality of the strike by its language teachers. The union in that case cited the Nichibei verdicts, and the Tokyo District Court backed the union, ruling that the strikes were perfectly legal.

Amazingly, the dispute at Nichibei Eigo Gakuin continues to this day, having been stalemated for nearly two decades. Management refuses to budge on pay-hike demands, despite having failed at their efforts to crush the union and having had all three dismissals overturned. Meanwhile, the union refuses to back down and continues the fight, ready to strike again if needed.

For Tesolat, a union that doesn’t strike is hardly a union. “Simply put, if you’re going to have a union and refuse to ever strike, don’t even bother setting up a union,” he says. “I’m not saying you have to strike, but you have to be willing to.”

Dorey notes that students at the Umeda school — the company’s Kansai flagship, where he and many other union members worked — formed a students group (seitokai) in 1998, gathering 100 signatures in support of the union. “The students even demanded negotiations with the company to put pressure on them to resolve the dispute,” he recalls.

Did members feel nervous going on strike the first time?

“We (felt a) natural awkwardness,” he says, “when leaving the classroom and when meeting (students) again the next time. We felt terrible for the students and really had to push ourselves and encourage each other to get through it. Luckily our students were very sympathetic.”

General Union’s fight at Nichibei, including determined, relentless strikes and other actions, should serve as a model for workers on how to muster the courage to build solidarity with coworkers and exercise their precious right to strike.

Article 28 of Japan’s Constitution guarantees the right to strike to all workers (the lack of that right for civil servants has yet to be challenged in court). This is one of the three so-called pillar rights for workers in Japan, or rōdō sanken: the right to solidarity, collective bargaining and collective action (including strikes).

I urge all workers to unionize and strike to protect and improve their working conditions without guilt, without apology. Many of the rights we enjoy today are thanks to strikes and other collective actions going back centuries. Workers have literally risked and given their lives to win this right. Strikes go back to ancient Egypt, and the history of industrial action is, in a very real sense, the history of the progress of civilization around the world. That progress outweighs whatever short-term inconvenience is caused to customers.

“I would say that striking is stressful, but without it, unions are toothless,” says Dorey. “In my own personal experience, too, I can say that the courts and labor commission have strongly upheld this right, even in the case of partial strikes. I think it’s important to ignore all the propaganda about striking somehow being ‘un-Japanese.’ Article 28 of the Constitution and Article 7 of the Trade Union Law are really strong protections for us, and they are there to be used.”

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as executive president of Tozen Union. She can be reached at tozen.okunuki@gmail.com. Labor Pains appears in print on the fourth Monday Community Page of the month.

Comments are closed