Expedia Japan recently released the results of an annual survey that corroborates the stereotype many folks have of the Japanese worker: In short, their work is endless and breaks are few and far between.

The travel company site surveyed 9,424 adults from 28 countries about paid holidays. You can see the full results here: bit.ly/yasumiheta.

But let’s back up a bit first. The Abe government has tried desperately to drive home policies to reform how we work, with the aim of offering an escape from the “worker bee” mode of labor. However, in the survey, Japan ranks dead last when it comes to the percentage of paid leave taken, at just 50 percent. So on average, Japanese workers take only half their allotted paid holidays.

Japan clinched the worst record on paid holidays by undercutting South Korea, which held the dubious title in 2014 and 2015, by just three points. In five countries or territories, workers took an average of all their paid holidays: Australia, Brazil, France (of course), Spain and Hong Kong, although the latter guarantees only 15 days by law, so it’s not as shining an example as the others.

Despite Japan coming in last in terms of the percentage of granted paid leave used, Japanese were also the least likely to complain that they get too few holidays, with just 34 percent saying so. The people who most longed for more holidays were the Spanish, even though the law grants workers 30 paid holidays and Spaniards tend to take off 100 percent of the days they are allotted.

Some 59 percent of Japanese workers feel guilty about taking holidays, putting Japan in second, just behind their worker-bee rivals south of the 38th parallel across the Sea of Japan.

Article 39 of the Labor Standards Act stipulates the clear right of workers to take paid leave. It recognizes paid holidays as something the worker can take freely when they choose, in principle. It seems that the guilt felt by workers comes from the fundamental misapprehension that paid leave is granted out of kindness on the part of the employer. Another reason is misplaced kindness — a fear of causing trouble or extra work for co-workers.

In my opinion, there is nothing virtuous about not taking paid holidays to minimize trouble for co-workers. The reason for this is that sacrificing paid holidays is contagious: New employees see you working without leave, and they feel they shouldn’t touch their holidays either. You are robbing your coworkers of their leave. If you are going to feel guilty, feel guilty about nottaking your paid leave.

Meanwhile, another study shows that 11 percent of people have taken leave from their school or company after the death of a pet. The website Shirabee asked 361 Japanese between the ages of 10 and 60 if they had ever taken time off school or work after a pet’s passing.

About a third of Japanese have a pet. For those who live alone or even in a nuclear family, a pet can be so much more than just that — something approaching a life partner. A 60-something friend confessed to me that “Conversations with my husband are boring, stifling, but I have Cha-kun (a Pomeranian). It’s a precarious balance, but without Cha-kun I might have divorced.”

The following comments were left on the aforementioned site:

• “After my cat passed away, I stopped going to university for two or three days” (woman in her 20s).

• “The day after our dog died, I took paid holidays because I was in no state emotionally. I couldn’t tell the company the real reason” (woman in her 40s).

• “The finch I’d had for a long time suddenly up and died. I was in shock and couldn’t work. I lied that my family member had suddenly died and took three days of compassionate leave” (man in his 30s).

Some of the accompanying comments give a good idea how much pet owners suffer when their loved one dies, and how they have trouble getting back on their feet. In Japanese, this feeling is called “pet loss.” It’s still true, however, that the atmosphere at many workplaces is such that it’s hard to ask for leave when a beloved pet passes.

Those who don’t keep pets may feel that, as one man in his 40s put it, “For an adult to take off work due to a pet violates common sense, while also causing trouble to others.” A woman in her 50s said, “I understand how painful it may be, but work is work, and an adult in our society must be able to switch gears properly.”

A handful of corporations have set up systems for pet consolation leave, as a benefit for their workers. Other firms have other unique paid leave allowances, such as “heartbreak leave,” with older workers getting more days of leave based on the thinking that they take longer to recover from a broken heart.

Some criticize such holidays as being too soft and spineless, harking back nostalgically to the intense, driven salarymen of the era of Japan’s breakneck postwar growth. Long hours without rest was a norm for an adult. Some may believe that guts can overcome any challenge, but extreme mental stress often leads to physical health problems.

Resting and being able at any time to rest are crucially important. To naysayers, I want to ask if a society would not improve if it told those suffering from a pet death or a break-up “You are in a bad state, so please get rest” and showed kindness, warmth and tolerance. Some might consider such compassion for those suffering the loss of a pet or a loving relationship too extreme, but I think the same logic is deployed in defense of child care leave and child sick leave.

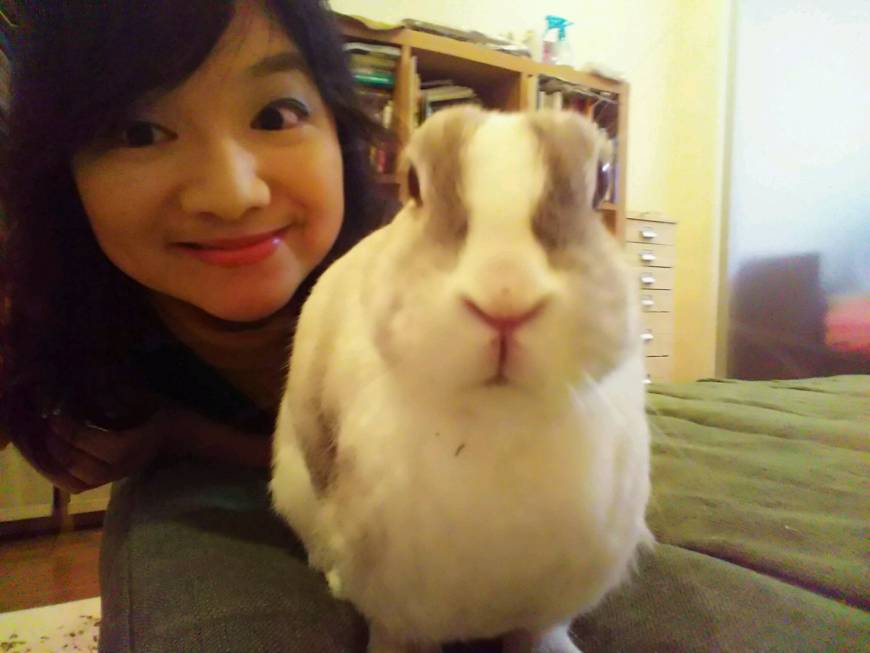

Forgive me for finishing on a personal note. I live with a 9-year-old white and gray rabbit named Haneko-chan. I have discovered and learned so much from her.

I often ponder our human society and the deep criminality and foolishness of politicians both here and abroad, and gloom fills my heart. If rabbits were in charge of things, we would see neither war nor environmental pollution. Their eco-footprint is as tiny as one of Haneko-chan’s front paws.

Early in the morning, rushed and miserable, I prepare to embark on a long, brutal day of work at my university. I look at Haneko-chan and see resigned loneliness as she watches me go. I have to force myself out of the door, against all my instincts to drop my bags and stay home with my granny bunny.

When she looks ill, I feel I must rush home after work as soon as possible, which often is not soon at all. Each time I cross the threshold of my home, I can’t wait to see my bunny’s ears perked straight up as she tries to discern who is intruding on her patch.

All this makes me realize how seriously we should take paid leave for pets.

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as executive president of Tozen Union. She can be reached at tozen.okunuki@gmail.com. Labor Pains appears in print on the fourth Monday Community Page of the month. Originally published in The Japan Times.

Comments are closed