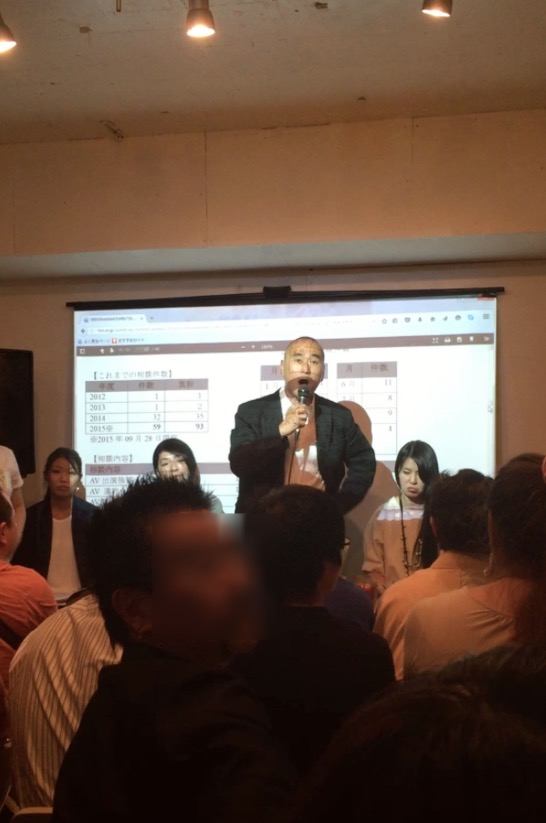

On May 4, a tiny cafe in Tokyo’s Koenji neighborhood was transformed into an informal meeting hall. Porn-film kingpins (and a “queenpin”) had called an “emergency meeting” to respond to a recently released report by Human Rights Now (HRN).

On March 3, the international NGO, which is based in Tokyo and has U.N. special consultative status, reported the results of an in-depth investigation into the pornography business in Japan. The report concluded that the industry had violated the human rights of women and girls through means such as blackmail, virtual enslavement and seeking illegal breach-of-contract damages from women who try to back out of films after being persuaded or duped into acting in them.

Porn industry bigwigs hosting the event this month struck back. Erotic fiction writer Kureichi Matsuzawa claimed the report has “smeared the entire industry with the rot of a few bad apples.” The hosts deftly played the woman card, accusing HRN of “painting a picture of actresses as helpless damsels in distress with no will of their own, and fostering discrimination against those in the industry who take great pride in their work.”

The hosts invited HRN to send a representative to defend the report, but the invitation went out only the night before. A representative of People Against Pornography and Sexual Violence (PAPS), a group that had cooperated with the study, attended to defend the report on HRN’s behalf. PAPS’ Kazuna Kanajiri had mustered the courage to turn up and managed to hold her ground against the very industry her group was trying to destroy.

Writer and former porn star Mariko Kawana spearheaded the event. More than a decade ago, she was famous in the world of porn for playing “beautiful older woman” roles (bijukujo-mono). She said at the event that in the roughly 400 porn films she had made, she was never coerced, duped or exploited.

“It was more like I was the one who yelled, screamed and made the director grovel on the ground whenever there was something screwy on the set,” Kawana said. She exuded power and charisma.

Goro Tameike was also present. A famous porn director as well as an external director of the major porn distributor SOD Create, Tameike also happens to be Kawana’s husband. He claimed he had experienced trouble with an actress on just a single occasion during the course of making about 1,300 porn films over a 22-year career. This power couple are industry leaders and represent the management perspective in the industry.

Two currently active porn actresses also attend as guests: Haru Imaga and Tsukio. One of them said, “I read the HRN report and was like, what industry are they even talking about? This report twists porn in a miserable way that doesn’t ring true at all.” Neither of them had a single bad word to say about the industry or their profession.

The only guest who broke ranks was porn actor Kohei Tsujimaru, who is also currently working. He contradicted everything Kawana said, wrecking the harmony of the united front the industry was trying to present as a counter to the HRN report:

Kawana: “Porn actresses come to act, not to have sex.”

Tsujimaru: “Nearly all male actors appear in porn films because they want to have sex.”

Kawana: “Neither I nor anyone around me has ever experienced the kinds of things depicted in the HRN report. Maybe it’s because I’m a strong woman and strong people tend to draw other strong people.”

Tsujimaru: “I know of one case where an actress tried to commit suicide after being forced to do something she didn’t want to do while working for an extremely famous porn distributor.”

Tsujimaru ruined the hosts’ carefully crafted consensus by assessing the report to be “not so bad.” The hapless hosts went for a diving catch: “Well, (the report) is not in line with your experience, Mr. Tsujimaru, is it?” I personally feel that Tsujimaru’s quiet but determined quips rang true and left the deepest impression among all the words spoken that day.

The air was thick with tension throughout the meeting. At one point, from the back of the room, came a booming baritone, interrupting the meeting: “Excuse me a moment! I have something I simply must say.”

The bald, impatient man was Kenji Kubodera, a former porn actor. The hosts replied, “Please wait 15 minutes,” but even after a quarter of an hour had passed, the man was given no opportunity to speak. Kubodera repeated himself dozens of times: “Chotto sumimasen,” (“Just a second”). As the crowd grew steadily more antsy, the hosts kept responding with “Chotto matte, ne” (“Just wait a moment”).

After 30 minutes, Kubodera could wait no longer and started shouting out his story from behind me: “I used to work in the porn industry as an actor under the pseudonym Kaminari Kozo (Thunder Kid). I was subjected to horrendous torture. They thrashed me mercilessly with a horsewhip.”

Tameike and erotic writer Kureichi Matsuzawa, also seated at the front, screamed back at Kubodera in the most vulgar, rude Japanese to shut up and get the hell out.

The back-and-forth bickering and screeching continued for a good portion of an hour. During the scuffle, Kubodera was led out of the room. About 10 minutes later, he managed to get back into the cafe and started again trying to tell his story of trauma and horror. Tension rose again and he was dragged out of the room, this time kicking and screaming.

I can only imagine what this man must have gone through on various porn sets during his career. Kubodera returned after his second eviction only to tour the room, offering apologies to each of us, scrunching his large frame into a piteous bow of contrition: “Sumimasen, sumimasen.”

Looking at Kubodera, clearly suffering mental anguish and instability, made me feel indignant toward Matsuzawa and Tameike. They hold such positions of strength that they are deaf to the reality that porn creates for countless actors and actresses whose names we will never know.

The cafe had too few fold-up chairs to accommodate the attendees, so many had to stand up for the entire time, which exceeded five hours. The place was packed like a Bernie Sanders rally. Actually, perhaps a Donald Trump rally would be more appropriate: It was hard to tell who was on the side of human rights and dignity and who was defending patriarchal bigotry.

I became so engrossed in the debate that time flew. This debate raised more questions than answers, offering no real closure. By the end, however, I felt that I could not concur with the industry representatives’ scripted narrative.

The first problem is that nearly all porn actresses sign outsourcing contracts as if they are private contractors. These gyōmu itaku contracts differ from regular employment contracts (rōdō keiyaku) in that they are not covered by labor law (except the Trade Union Law).

Kawana stressed that the actresses are private contractors so they have a right to speak up. Later she tweeted: “If porn actresses are employed with labor contracts, they will enter into highly exploitative relationships, vulnerable to all manner of harassment from their employers, long work hours, lower take-home pay (since they will get benefits), and may even enter the ranks of the working poor.” Her Twitter feed read like a negative campaign being waged to stop actresses signing labor contracts.

I have to say, however, that Kawana’s equating of labor law with depriving workers of freedom is based on a self-serving misunderstanding. I cannot emphasize enough: Labor law binds employers, not employees.

Labor laws oblige employers to stipulate working conditions; pay wages; allow breaks, days off and holidays; manage work hours; pay overtime rates for overtime work; sign an Article 36 contract with a worker’s representative before even asking for any overtime work; enroll employees in shakai hoken health and pension schemes, unemployment insurance and rōsai workers compensation; draft shūgyō kisoku work rules; ensure worker safety; grant maternity and child care leave; and negotiate collectively when a union requests it.

The breach-of-contract penalty that many gyōmu itaku (outsourcing) contracts contain is also illegal in a labor contract (under Article 16 of the Labor Standards Law). Kawana tweeted: “I think choosing protection of actors under labor law is a bad move. Porn actresses under the current outsourcing contracts have the right to accept or refuse to act in any particular film, and the production company cannot give orders. So coercion is unlikely. But with an employment contract (koyō keiyaku), the production company can give work orders, so the actress cannot refuse to act in a film.”

Another self-serving misrepresentation. Does she think that labor law gives the employer the right to give any order they like? Or that the employee is obliged to comply with all work orders, no matter how ridiculous? She is confusing an employment relationship with slavery. I am concerned that the misinformation such a powerful player like Kawana is disseminating online will mislead many porn actresses into thinking that labor law would deprive them of their liberty.

But why is a porn heavyweight like Kawana spending precious waking hours at the keyboard blasting away at labor law? Because although she was an actress, today she is management. For management, the application of labor law is an intolerable burden — the type of pain in the ass that usually only the actresses must suffer. It’s natural that she would want to avoid its restrictions if at all possible. It makes me very uncomfortable to hear this industry representative, who happens to be a former actress, pretend to speak on behalf of all porn actresses.

The fact that neither Tsukio nor Imaga — both active porn stars — said nothing negative during the entire event should come as no surprise: No employee could publicly say how they really feel about their company with the company president sitting beside them.

What about those penalties for breach of contract? One production company sued an actress for ¥24 million for breach of contract after she pulled out early from a film. The Tokyo District Court rejected the claims on Sept. 9, ruling that “regardless of what form the contract took on paper, the reality of the relationship was one akin to employment.”

What this case confirms, then, is that the type of contract is determined not by what is written on paper but by the reality of the employment situation. Note that, despite Kawana’s claims to the contrary, the court’s determination that the actress had a labor contract is what granted her the freedom to refuse to act in the film. Labor law, it seems, can even protect porn actresses.

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as executive president of Tozen Union. Labor Pains appears in print on the fourth Monday Community Page of the month. Story originally published in The Japan Times.

Comments are closed