On May 25, a man wielding a saw attacked and wounded 19-year-old Rina Kawaei and 18-year-old Anna Iriyama, two members of bumper girl group AKB48, and a male staffer at an event where fans get to shake hands with their AKB idols.

Fortunately the injuries were minor, but fans were shocked. The victims and their AKB48 comrades must have been terrified.

AKB48 has achieved superstar status, churning out serial million-selling CDs on the back of its image as a band of “idols you can meet.” The members tour the country, shaking fans’ hands, having their photos taken with them and generally interacting with their supporters. (One reason they sell millions of CDs in this post-CD world is that each package includes an IOU for a handshake with the AKB48 girl of your choice.)

The two AKB48 members were injured during work. At a company, such an injury would qualify the worker for rōsai, or industrial accident insurance, colloquially known as workers’ comp. But are members of this group, the brainchild of an entertainment agency, in fact workers? Are they eligible for rōsai?

The Industrial Accident Insurance Law only covers workers, or rōdōsha.

The law considers some people to be rōdōsha even when they don’t have an employment relationship. Most celebrities, actors, singers and other performers in Japan work without written contracts.

Just calling someone an entertainer doesn’t really tell you all that much. There are a lot of different types of “entertainer” depending on their position or status, whether the person belongs to a major talent agency, and the medium and content of their work.

Veterans may be able to call the shots, but newbies usually have little choice but to do what they’re told. So, determining rōdōsha status can be tricky and must be done on a case-by-case basis.

The then Ministry of Labor issued a directive on July 30, 1988, listing the criteria to use when determining the employment status of entertainers. That directive said that if all four of the following conditions are met, then the person is a private contractor, but rōdōsha status is recognized if the entertainer fails to fulfill even one criterion.

1. The entertainer’s art, popularity or other individual characteristics are important, and the songs or acting she/he provides cannot be provided by an understudy.

2. The remuneration the entertainer receives is not based on hours worked.

3. The entertainer is not forced to work certain hours related to production, even if there are set scheduled times for rehearsals, performance and other similar work.

4. The contract format is not an employment contract.

So let’s apply these criteria to the two AKB members who were attacked. Are they rōdōsha?

Starting with point 1, their rōdōsha status might be denied if it is clear that no understudy can replace them in public performances if something were to happen to them.

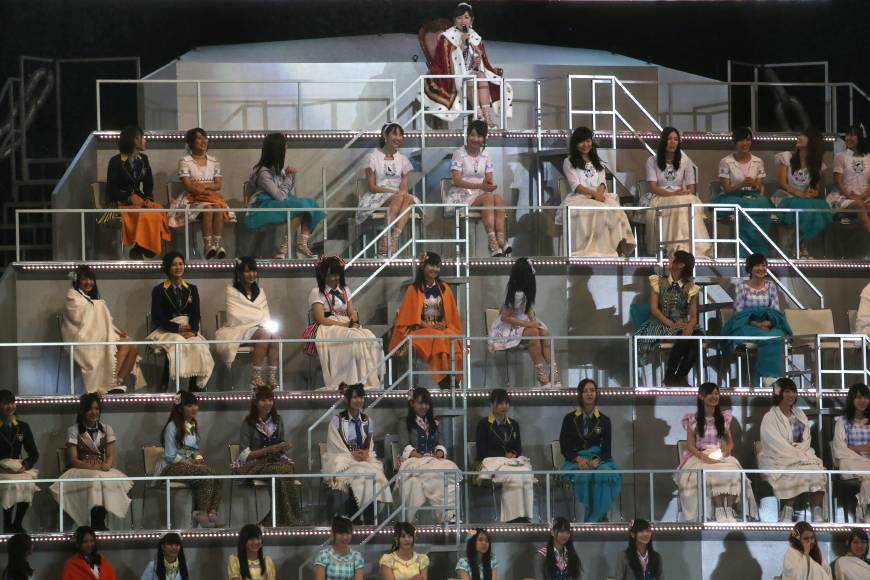

The ranks of AKB and its sister groups now number more than 300, including spinoffs in Nagoya (SKE), Osaka (NMB), Fukuoka (HKT), Jakarta (JKT) and Shanghai (SNH). I wonder what percentage of the members of these groups are so central and well known that they cannot be replaced by understudies. I also wonder whether Kawaei and Iriyama could be judged to be un-understudy-able. I’m sure their fans, at least, would consider them irreplaceable.

Moving on to No. 2, neither their pay nor how they are paid are public knowledge, so we cannot say whether they are paid for hours worked; nor do we know the pay disparity between the most and least popular members. But it’s hard to imagine entertainment work being paid by the hour: It can take a whole day to shoot one scene of a TV drama or movie, or taping may go more smoothly and finish earlier than expected. Dates and venues are, in a sense, mere formalities. We could compare pay if there was a clear timetable that applied to all the entertainers, but usually this is not the case.

For criterion 3, it is clear that AKB group members perform and offer handshakes under the orders of management, meaning individual theater management and franchise creator and music producer Yasushi Akimoto. This means that each member has no freedom or discretion to choose their work, and must be at certain places and times. I believe this means that both popular and not-so-popular members would have a strong case for claiming rōdōsha status.

AKB group members are perpetually embroiled in intense competition, vying for rank and center stage. They switch position in a manner similar to how workers are transferred, they are demoted from regular members to “trainees,” and management always makes sure to pit them against each other to add a competitive edge to the whole experience.

A look at this system reminds me of the predicament of ordinary workers at a company. Perhaps fans who work at ordinary companies project their feelings onto the members of AKB, who are treated similarly to company employees.

From the above, I think it is clear that AKB members would and must be recognized as rōdōsha. Although some factors, such as their fame and method of payment, may dilute the rōdōsha status of the members, the fact that they work under orders and are held to schedules they are not free to choose suggests that they are employees, even if they have no formal employment contract. And since they are rōdōsha, their right to workers’ comp should also be recognized.

Finally, it perturbs me that Akimoto, effectively the chief executive, has made no comment on the attack. AKB members themselves have blogged and tweeted that they don’t want to let the incident threaten their interaction with their fans, and that they want to continue the handshake events.

Not one naysayer, not one sulk or suggestion of self-pity, not a single negative tweet, not a single “let’s lay off for a bit and retrench” has leaked out from the AKB48 members since the violent incident, but it’s hard to imagine that this brutal attack didn’t horrify and terrify the girls. I can only venture a guess that perhaps they are under orders to stay positive in the wake of the attacks: under orders — like workers.

In January 2013 I penned a Labor Pains column about the weak position of AKB members and how their only hope for negotiating from a position of parity with management would be to unionize. It’s hard not to come to the same conclusion again today.

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as executive president of Tozen Union (Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union). She can be reached at tozen.okunuki@gmail.com. On the second Thursday of each month, Hifumi looks at cases in Japan’s legal history to illustrate important principles in labor law. This month’s column has been rescheduled due to a World Cup special on Thursday.

Comments are closed