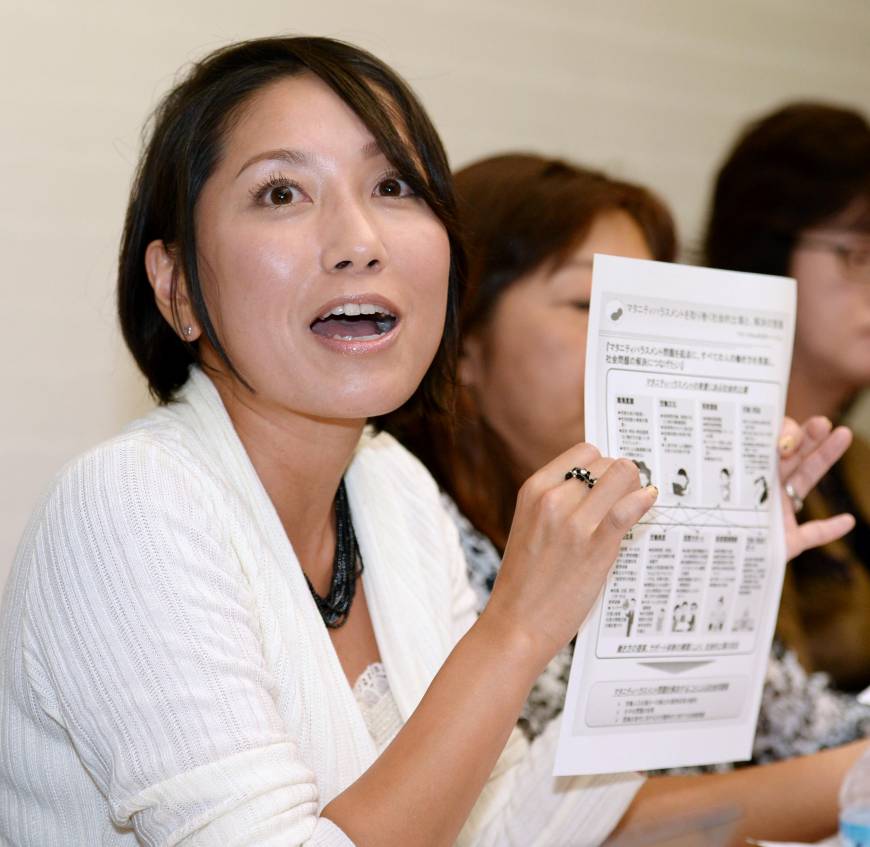

Last Thursday’s Supreme Court verdict in the “maternity harassment” case brought by a physical therapist in Hiroshima was the first of its kind, overturning decades of business-friendly jurisprudence along with rulings from the district and high courts.

As I mentioned in last year’s September Labor Pains (“Mata-hara: turning the clock back on women’s rights”), the word mata-hara is short for maternity harassment, just as seku-hara and pawa-hara refer to sexual harassment and power harassment, respectively. Maternity harassment means workplace discrimination against pregnant or childbearing women, including dismissal, contract nonrenewal and wage cuts.

The problem is that the employer also removed her fuku-shunin title. She had the baby and took child care leave. When she returned to work, the hospital put her back on the home-visit rehabilitation team but did not restore her title. She found herself working under someone many years her junior. She also lost the “middle-manager allowance” that had gone with the title.

She sued the employer, technically a health co-op named Hiroshima Central Health Cooperative, for damages based on violation of Article 9.3 of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act and Article 10 of the unwieldy Act on the Welfare of Workers Who Take Care of Children or Other Family Members Including Child Care and Family Care Leave. She also claimed gender discrimination.

Hiroshima District Court, on Feb. 23, 2012, and Hiroshima High Court, on July 19 the same year, both rejected her claims outright, the lower court ruling that “the measure was taken within the legitimate realm of discretion by the employer/defendant based on personnel placement needs, administration and work duties after a request by the plaintiff for a switch to less demanding work due to her pregnancy, while the plaintiff never objected to the shift to a lighter workload.”

Last Thursday, however, the Supreme Court basically said, “No, no, no, we’re not going to do it that way.” The highest court overturned both lower court verdicts and sent the case back down to the high court — in effect, ordering it to change the verdict.

“Demotion and other unfavorable measures violate the Equal Employment Opportunity Act unless the pregnant woman consents to it freely and of her own accord, or if special circumstances exist in terms of smooth administration or personnel placement that make it unavoidable,” said the Supreme Court, ordering the high court to consider whether such special circumstances existed.

The landmark quality of this case cannot be overstated. If women can be demoted for getting pregnant, then women who care about their careers will hesitate to have children at all.

What shocked me, however, was that women around the country, far from applauding the verdict, are frothing at the mouth to attack the victim. At least that is what I have seen and heard in Internet chat rooms and on TV. Some samples:

“She asked for the lighter workload so she cannot object to a demotion.”

“Why the hell should she hold the same position and work conditions even though she is doing easier work?”

“I feel sorry for her co-workers who had to take up the slack while she was on maternity leave.”

It seems that such critics believe that slave-driven salarymen toiling until late at night and on weekends with no thought for their personal lives represent the ideal of what work should look like. There seems to be a sense that overwork is somehow unavoidable, so if women want to work, they must accept the same brutal conditions. Thus, having a child is a private matter that causes inconvenience to the company.

This is in line with what is called the Showa no ossan (Showa Era old man) model of the perfect worker. It fits in with the man-work-woman-stay-at-home ideal of yore. Japan’s current tectonic demographic shift can ill afford such an anachronistic gender-based division of labor.

The business world is panicking as the population of children shrinks and the ranks of elderly swell. The Japan Association of Corporate Executives has called on capable women, young people, old people — even foreigners — to “join the labor force so that Japan’s economy and society can be maintained and developed.”

It’s crucial to understand that mata-hara is not only a women’s issue. It is one that involves all workers — and everyone else.

It is not that women should work as hard as men; nor should they have to quit if they want children. Rather, we need to challenge the slave-driven salaryman model. We need to overturn the self-sacrificing worker-drone mentality and create a more humane and human workplace for men and women alike.

Hifumi Okunuki teaches at Sagami Women’s University and serves as executive president of Tozen Union (Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union). She can be reached at tozen.okunuki@gmail.com. On the fourth Thursday of each month, Hifumi looks at cases in Japan’s legal history to illustrate important principles in labor law.

Originally published in the Japan Times.

Comments are closed