BY HIFUMI OKUNUKI

They started performing on stages in Tokyo’s Akihabara electronics district, and today their ubiquity is unrivaled. The current flavors of the month pepper the TV schedules and covers of weekly magazines all year round. In Tokyo, you can’t swing a carrot without hitting a giant poster of one or a bunch of the all-grinning, all-dancing “Vegetable Sisters.” AKB48 are, hands down, the busiest and most successful girl group in Japan.

They have spawned spinoffs in other cities: SKE48 from Nagoya’s Sakae district, NMB48 from Osaka’s Namba neighborhood and HKT48, from Fukuoka’s Hakata. Last year, their inspiration transcended national borders and a testy territorial dispute as the franchise set up shop in Shanghai as SNH48, hot on the heels of the group’s first foreign foray, Jakarta’s JKT48. Another offshoot, TPE48, is planned for Taipei.

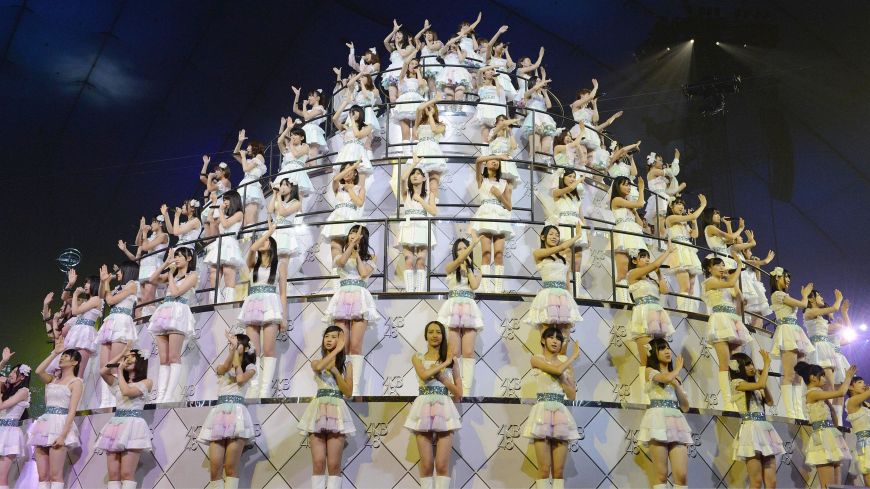

The original AKB48 troupe now numbers 87 members (that’s including “trainees”), making it the largest pop group in the world. Among these teenagers and 20-somethings, cut-throat competition has arisen alongside gross disparities between the fortunes of the most popular, the less so, and those whose day on the big stage just never comes.

Their management prohibits the girls from having romantic relationships, with a contract clause stating that “Unrequited love is permissible, but you cannot return the affection.” Several members have been pushed to resign or “graduate” after photos leaked out revealing the girl was dating.

Quite recently, the much-loved Yuka Masuda announced her sudden resignation from the group after stepping over the no-love-life line. Photos splashed all over a weekly magazine suggested she had spent the night at a male celebrity’s home. Though not officially “dismissed,” it is clear that decisions in her personal life cost her her job.

Although not all scholars agree, I believe even celebrities such as AKB48 members are protected by labor standards law. This month I’d like to examine two questions: 1) Does the law permit chastity clauses? and 2) Can an employer fire someone for violating such a rule?

Labor contracts, like all contracts, are predicated on the assumption of agreement between two parties. But that does not mean that anything goes when it comes to their provisions. Four conditions must all be met to legitimize each and every term of a contract: kakuteisei (determinacy),jitsugen kanōsei (achievability), tekihōsei (legality) andshakaiteki datōsei (social justification).

It is the fourth, shakaiteki datōsei , that concerns us in the AKB48 case. This concept entails general ideals of morality and justice, specifically kōjo ryōzoku (public order and morality), a crucial and broadly ranging legal principle enshrined in Article 90 of the Civil Code.

Contract terms that violate kōjo ryōzoku are invalid. Textbook examples include: paying for a crime; terms that violate fundamental human rights, such as gender bias; terms that restrict individual freedom; and those that violate social morals such as human trafficking, prostitution or geisha provisions. While traditional geisha exist within the scope of the law, asking an employee to “entertain” a client does not.

Most would consider it an unjustifiable invasion of privacy if an ordinary company prohibited their employees from taking a lover. Apologists for the AKB48 chastity clause argue that a girl’s value as an idol is compromised if it becomes known she has a boyfriend because her job is to “sell fantasies” to male fans. In fact, quite a few fans have commented on chat sites that they felt “betrayed” and “lied to” by AKB members who began dating.

I have a different view. Teenage girls and women in their 20s are at an age when their love life is the most exciting — a time that’s arguably the best chance to experience the ups and downs of the adventures of love and life. Their managers and producers surely don’t have the right to deprive them of that opportunity.

Some might say that if the girls want love, they shouldn’t join the group in the first place. This argument could be and is used by the worst corporate exploiters to justify just about any illegal contract provision.

So can you be fired for violating such a provision, for a reason grounded in your private life? Dismissals must have “objective and rational grounds” (Labor Contract Law, Article 16).

Asahikawa District Court on Dec. 27, 1989, ruled against a company (Hankiko Setsubi) that fired a female employee but not a male one after discovering the two were committing adultery.

Management reasoned that even if it does not interfere with work, “adultery adversely affects the company’s moral order, hurts coworkers’ motivation, and makes the president lose face.” While acknowledging that the woman’s actions were illegal and immoral, the court said that only specific damage to the running of the company constitutes hurting the workers’ moral order or motivation, a condition not met in this case.

Thus judicial precedent prohibits disciplinary action for problematic personal behavior that has no connection with work duties. Meanwhile, only if such personal actions severely damage a company’s overall reputation can they be considered to have seriously damaged the company’s moral order.

It is clear that the AKB48 chastity clause fails to meet the court’s criteria for legitimate grounds for dismissal.

To members of AKB48: If you want to fight for your right to live and love freely, you’ll need solidarity with your fellow band members, so why not establish a union? The “Vegetable Sisters” should be sisters in deed as well as name — not rivals.

Hifumi Okunuki teaches constitutional and labor law at Daito Bunka University and Jissen Women’s University, among others. She also serves as paralegal for Zenkoku Ippan Tokyo General Union. Usually on the third Tuesday of the month, Hifumi looks at a famous case in Japan’s legal history to illustrate an important principle in labor law.

Comments are closed